When Scripture Enters the Courtroom: Manusmriti, Criminal Justice and India’s Constitutional Crisis

India’s constitutional framework rests on a foundational premise: Criminal Justice must be governed by enacted law and constitutional values, not by religious scripture or moral theology

India’s constitutional framework rests on a foundational premise: Criminal Justice must be governed by enacted law and constitutional values, not by religious scripture or moral theology.

Yet, this premise has been seriously unsettled by a recent Sessions Court judgment from Bahraich, Uttar Pradesh, where the death penalty was awarded while invoking verses from the Manusmriti.

The controversy surrounding this judgment is not about the gravity of the crime alone. It raises far deeper concerns about secularism, equality before law, judicial discipline, and public confidence in the justice delivery system.

In December 2025, the Additional Sessions Judge at Bahraich sentenced Mohammad Sarfaraz to death for murder arising out of the October 2024 communal violence case famous as R G Mishra murder case.

In justifying the need for deterrent punishment, the judgment relied upon a shloka attributed to the Manusmriti: “दण्डशास्तिप्रजाःसर्वादण्डएवाभिरक्षति।दण्डसुप्तेषुजागर्ति, दण्डंधर्मविदुर्बुधाः”— translated as, “Punishment governs all subjects; punishment alone protects them; punishment remains vigilant when all sleep; the wise declare punishment to be the embodiment of dharma.”

This verse, generally traced to Chapter 7 (Verse 18) of the Manusmriti, was used to emphasise the necessity of harsh punishment for maintaining social order. While the sentiment of deterrence may find echo in modern penology, the source from which it is drawn is constitutionally troubling.

The Manusmriti is an ancient smriti text, dated by scholars to roughly 200 BCE–200 CE, which lays down social and legal norms rooted in varna hierarchy and gender subordination. It explicitly prescribes differential punishments for the same offence depending on caste status, declaring, for example, that penalties for Shudras be harsher and those for Brahmins comparatively lenient.

Women are repeatedly described as requiring lifelong guardianship. Such provisions stand in direct opposition to the egalitarian foundation of modern constitutional law.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasised that ancient religious texts, however significant culturally, cannot be elevated to legal authority in a constitutional democracy.

This incompatibility was recognised even during the Colonial Rule. Under Warren Hastings’ Judicial Plan of 1772, Hindu and Muslim personal laws were confined to civil matters such as marriage, inheritance, and religious usage, while criminal justice followed a uniform framework.

Lord Cornwallis’ judicial reforms of 1793 consciously moved away from religiously derived punishments, establishing circuit courts and seeking consistency and proportionality in sentencing. Colonial administrators viewed scriptural punishments as arbitrary and incompatible with governance based on uniform rules.

The distancing of criminal law from religious authority became more pronounced under Lord William Bentinck. Through a series of regulations between 1829 and 1834, the role of religious law officers ‘pandits and qazis’ were effectively eliminated from criminal adjudication. The culmination of this process was the enactment of the Indian Penal Code in 1860.

Drafted under the leadership of Thomas Babington Macaulay, the IPC explicitly rejected ancient religious laws in favour of a rational, secular, and uniform criminal code. Macaulay was unambiguous in his assessment that traditional Hindu and Islamic criminal laws were “wholly unfit for a modern society” and incompatible with equality before law.

Independent India inherited and constitutionalised this secular approach. Articles 14, 15, and 21 of the Constitution guarantee equality before law, prohibit discrimination on grounds of religion or caste, and mandate that deprivation of life or liberty must occur only according to procedure established by law.

In S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994), a nine-judge Bench of the Supreme Court held that secularism is part of the basic structure of the Constitution, declaring unequivocally that “the State has no religion” and that governance must remain neutral in matters of faith.

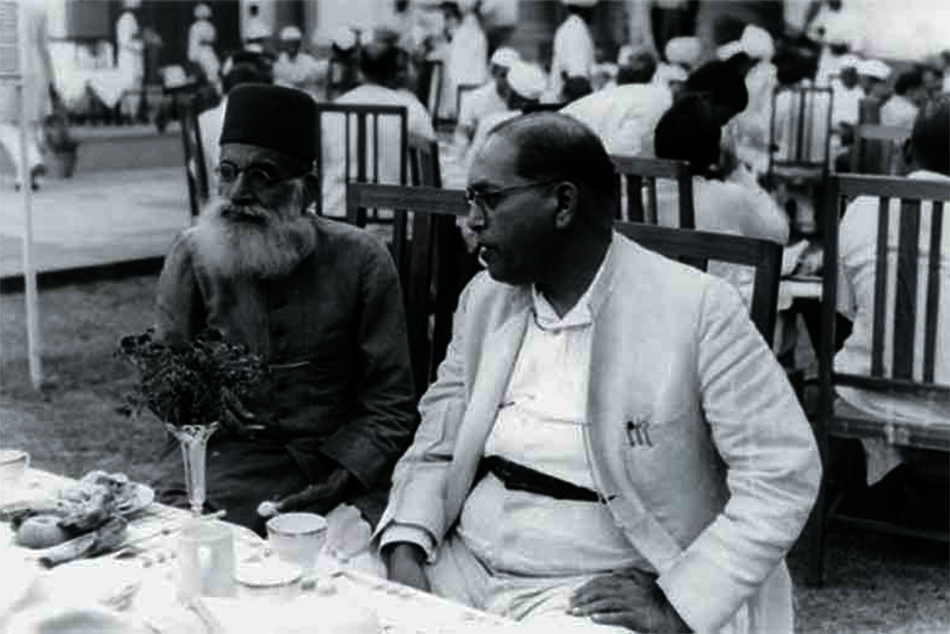

Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the principal architect of the Constitution, was acutely conscious of the dangers posed by texts such as the Manusmriti. On 25 December 1927, during the Mahad Satyagraha, he led the public burning of the Manusmriti, condemning it as a text that sanctified caste oppression and inequality. The Constitution he later drafted was designed as a radical departure from such normative frameworks, replacing graded hierarchy with equal citizenship.

Indian courts have occasionally referred to the Manusmriti, but historically such references have been illustrative or critical, not normative.

In Sarla Mudgal v. Union of India (1995), while examining the issue of bigamy through religious conversion, the Supreme Court referred to certain verses of the Manusmriti to highlight the historical subordination of women under traditional Hindu law.

The Court made it clear that such norms stood superseded by constitutional guarantees, observing that personal laws must yield to “constitutional values of equality and dignity.”

The concern arises when religious texts are invoked not merely to describe historical injustice but to justify contemporary criminal punishment.

Sentencing jurisprudence in India has been carefully developed to prevent precisely such arbitrariness. In Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980), the Supreme Court held that the death penalty may be imposed only in the “rarest of rare cases,” emphasising that sentencing must be based on “well-recognised principles” and a careful balancing of aggravating and mitigating circumstances. The Court warned that punishment cannot rest on emotion or moral indignation but must be “rational, principled, and guided by law.”

Judicial discipline has been equally emphasised. In State of Rajasthan v. Prakash Chand (1998), the Supreme Court cautioned that “judicial independence does not mean freedom to act arbitrarily” and that judges must not allow “individual predilections” to colour judicial reasoning. Courts, the judgment stressed, derive legitimacy from adherence to law, not from personal belief systems.

Invoking a religious scriptureparticularly one historically associated with hierarchyin criminal sentencing risks undermining secularism by privileging one faith’s moral universe over others. In a communally sensitive case, such reasoning can deepen perceptions of bias and alienation among minorities. Justice must not only be done but must manifestly appear to be done; reliance on religious authority erodes that perception.

The rule of law depends as much on legitimacy of reasoning as on correctness of outcome. Justice H.R. Khanna, reflecting on the role of courts, famously observed that judicial authority flows from fidelity to law, not from popular sentiment or moral fervour. When courts begin to draw upon scripture rather than statute, they risk weakening the constitutional foundation that gives their judgments authority.

India’s judiciary now stands at a critical juncture. Cultural and religious texts may hold social or philosophical value, but criminal courts are governed by the Constitution alone.

Punishment must be justified by law, evidence, and constitutional principles and not by ancient scriptures the Constitution was expressly designed to transcend.

To preserve secularism, democracy, and trust in justice, courts must reaffirm a simple truth- in the Indian Republic, the Constitution, not Manusmriti, is the final authority.

[The writer, Shahnawaz Ahmad is Assistant Professor of Law, Crescent School of Law, Chennai, and former Assistant Professor of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU)]

Follow ummid.com WhatsApp Channel for all the latest updates.

Select Language to Translate in Urdu, Hindi, Marathi or Arabic

Dr Ambedkar’s Critique of Islam and Muslims: A Scholarly Analysis